Making Things Waterproof – IP Ratings Explained

Introduction

When talking about electronics enclosures, “waterproof” can be a very ambiguous term. Your smart phone will probably be just fine if you spill a glass of water on it but may not fare so well after 30 minutes at the bottom of a pool. Enter IP ratings. IP stands for “ingress protection” and is an international standard used to quantify the effectiveness of an electronics enclosure against dust and moisture. When designing an electronics enclosure, it is important to identify the enclosure’s use environment early on. This will allow you to include the necessary design elements to ensure the electronics can survive where they are needed. A device that is meant to sit in your house and stay dry will need a much lower IP rating than a device that is meant to be worn while swimming.

IP Ratings

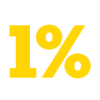

You may have seen some consumer electronics labelled “IP6x waterproof” or similar, but manufacturers rarely include a detailed description of what that means. So what do these numbers mean? Here is a helpful chart from nemaenclosures.com.

Although most laptops are not IP-rated, they would typically fall in the IP5X category, along with consumer products like digital projectors. You won’t be able to touch sensitive components with your finger, but spill a cup of water on your computer while it's open and water will seep into the enclosure through the keyboard and cause trouble.

Many athletic watches have an IP67 rating. They are designed to be used while swimming, so they can survive being submerged in water between 15cm and 1m deep for 30min or more. However, if they fall to a depth beyond that, the water pressure will likely be too great for their seals and water will eventually make its way into the device.

Most consumer products do not require anything above an IP67 rating. However, some devices designed to be used for deep sea photography or similar applications will require an IP68 rating.

Options for waterproofing

For waterproofing a device to a certain IP level, we have a variety of options—we’ll review a few below.

Potting

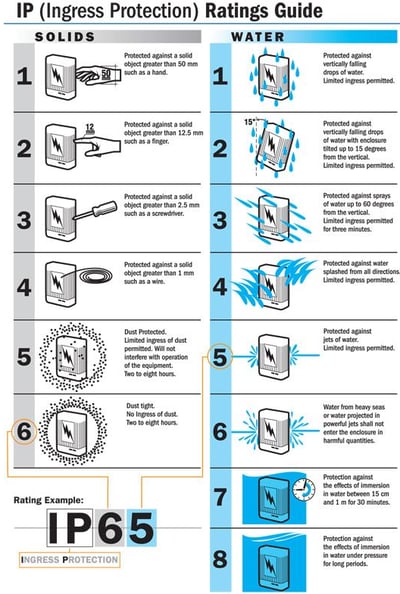

Potting is a process of filling an electronics assembly with epoxy or silicone gel. This process is especially useful in high voltage assemblies, where it can prevent electrical shorts and accidental current discharges. Potting is also recommended if your product is likely to experience a high degree of shock and vibration. The hardened gel encapsulant can hold components in place when the assembly experiences an impact.

Potting can be a sure-fire way of keeping water away from your electronics, but this also depends on the chosen potting material. Some silicone potting compounds seep low levels of moisture from the environment. Others are excellent insulators and prevent your electronics from releasing heat. In motor stators, this could be a great way to overheat your coils and burn out motors. For that reason, special heat-conductive compounds are often used for potting electronics that still need to dissipate heat.

Potted Enclosure

Conformal Coating

Conformal coating is a process of coating your PCBA with a thin polymer film to protect components from dust, moisture, and chemicals. The coating can be applied in a variety of ways including brushing, spraying, and dipping and the chemical used can range from acrylics to silicones and parylene. Although this process does not provide the same level of protection as potting, it can be more cost effective and appropriate for many applications and provides less of a thermal insulation barrier. Thinner coatings, like parylene, can even provide a degree of biocompatibility for electronics used on or within the body.

As with potting, immediate issues and pain points when using conformal coatings include connections with the outside world. Data and power ports can’t always be potted or coated but still present conductive surfaces that could come in contact with environmental moisture— they will need to be masked in some fashion prior to applying a coating.

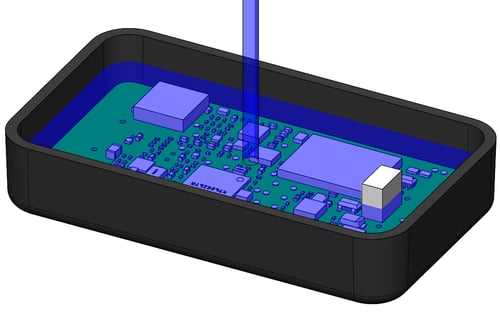

Sometimes electronic devices need to be easily disassembled, either to repair components or to replace components such as batteries. In this case, it may make the most sense to use a gasket to seal your device.

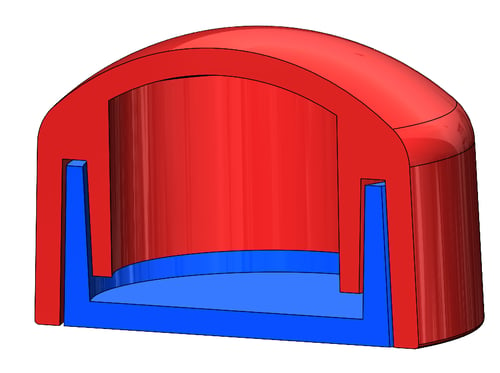

Gaskets come in two primary forms: face seals and radial seals. Face seals are those in which the sealing surfaces are normal to the axis of the seal, as shown below.

Face Seal

Face Seal

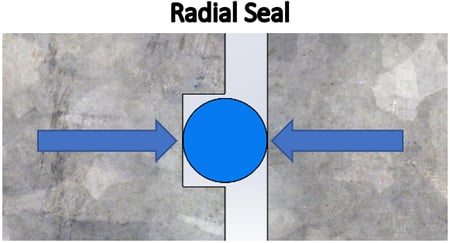

Radial seals are seals in which the sealing surfaces are normal to the radius of the seal. As shown below- these types of seals are typically used on parts such as bearing seals and pistons. We’ve also used them effectively in dive lights and seen them used in other IP68 camera housings.

|

|

For extreme environments, gasket-sealed enclosures can be paired with conformally coated electronics. This acts as dual protection against flooding of the case and electronics and also against condensation from humidity that is either already present in the enclosure or any that seeps through your enclosure.

When using a gasket, it is important that you ensure your device provides even clamping force across the entire surface of the gasket. If clamping force is not consistent across the gasket, it is possible to have water bypass the seal in areas where it is not compressed fully.

Other Sealing Methods

There is a wide variety of sealing methods used by manufacturers that can permanently seal enclosures. You’ve probably encountered plastic cases with lip-and-groove features that mate together during final assembly. Quick-curing adhesive, either applied by hand or a robot, provides the permanent seal. As with all cured adhesives/coating, including those used in potting and conformal coating, this step can add time and cost to the assembly process—on top of sometimes making a mess.

We occasionally see enclosures that are ultrasonic welded, which is a neat process of vibrating two halves of an enclosure to melt them together at the seam. This avoids an adhesive/curing process and can be a good option for plastics with low surface energy (those that don’t work well with most adhesives). This type of seal is not typically considered IP67 despite producing what looks like a very solid and even joint. The momentary sealing vibration can also damage internal parts.

A less permanent sealing method used in consumer products is an external gasket or shell. Some personal care items house their electronics in a simple lip-and-groove style solid plastic case that is not inherently watertight. A pre-molded silicone or TPE shell is stretched over the rigid case and, not unlike a rubber glove, prevents moisture ingress.

For low levels of ingress protection, not providing IP67 or IP68 waterproofing, it’s good to remember that simply designing a “maze” (ie: lengthening the ingress path) can go a long way! A cheap solution to protecting from spills or light rain might simply mean creating an unsealed case that resembles an upside-down cup. Fortunately for us, few spills fill upward!

A long maze-like ingress path, as shown here, can provide the minimal ingress protection needed on many consumer products.

A long maze-like ingress path, as shown here, can provide the minimal ingress protection needed on many consumer products.

Testing

Most ingress protection testing should be performed by an accredited lab. It is difficult to set up many of the IP tests because they require water to be sprayed at the device at specific pressures and angles. However, IP67 testing is easy to perform in-house. All you need is a container that is large enough to hold your device and deep enough to hold 1m of water—and it doesn’t need to be a pool.

When performing IP67 validation at BES, we will often place water sensitive paper inside enclosures. This color changing material helpful for determining the presence and location of water ingress. Below is an image of a polycarbonate tube that BES uses to perform IP67 testing in our lab. This setup uses simple parts available from most hardware stores and lets us easily achieve a constant 1.4-1.5psi of water pressure over a defined test period (usually 30 minutes).

1 meter of water in a transparent tube. Device under test (DUT) is connected to the yellow rope for quick retrieval.

Conclusion

There is a lot to consider when deciding how and to what degree to seal your electronics enclosure. To avoid any product delays, it is essential to have early planning, be very clear about your use environment, and get engineering involved early so that any seal-compromising design elements are identified before the project gets too far along. Aiming for a higher IP rating can add significant cost to your product, in the form of unit cost, design time and increased size of the device. As you get to the upper range of IP ratings, it may be necessary to employ multiple of the above methods to ensure your unit passes testing. The IP rating system should not be thought of as a linear system where more water exposure automatically relates to an increase in protection and cost. A unit that is exposed to prolonged steam in a bathroom setting will require different protection than a unit that is occasionally submerged in water for a short period of time. Being very clear about your use environment will save you on both design time and unit cost in the long run.

References

https://www.nemaenclosures.com/blog/ingress-protection-ratings/

https://www.electronicsb2b.com/headlines/learn-latest-developments-conformal-coatings/

.svg)